Color correction is one of the most rewarding stages of post-production – largely because it allows us as filmmakers to breathe new life into our projects from a visual standpoint. At the same time, it can be one of the most frustrating stages of post, as many filmmakers find themselves struggling tiresomely to find the right look and the best way to implement it. Like any other facet of filmmaking that is both creative and technical, color correction needs to be approached methodically and purposefully in order to achieve the best results in a short amount of time.

I’ve color corrected hundreds, if not thousands of projects, and there is no question that the projects that I was able to do the best work on also were completed in the shortest amount of time. Now, I’m not suggesting that you rush through the color process, or that there aren’t projects that call for a lot of time in the grade… But in many cases, a shorter color process is a good sign, as it shows that the filmmaker has truly identified the look they want to achieve, and has streamlined their process in the color suite to maximize results.

With that in mind, here are my 7 tips for speeding up your color process while improving your creative output:

SHOOT FOR THE GRADE

Some of you that are reading this are not only colorists, but also directors or DPs. And if you fall under the general “filmmaker” umbrella in any way, it’s important to recognize that your ability to achieve great results in the color suite starts during production.

Technically-speaking, it goes without saying that you (or your DP) must understand which settings, color spaces, picture profiles, and codecs are going to give you the best results in post. You essentially need to know the breaking point of your camera, and do enough camera tests to figure out which combination of settings will be most conducive to the look you are after… And sometimes the most obvious choice isn’t always the right one.

For instance, you might be tempted to shoot in a Log color space on your DSLR (since that’s what many filmmakers recommend), but through testing you may realize that your camera will actually deliver better results if you shoot in Rec. 709. Choices like this may sound counter-intuitive on paper, but in fact there are some cameras – namely certain DSLRs – that don’t handle Log color very well, and this is something you need to take into account on set.

This is of course just one example, but the overarching point is that you need to run tests for yourself during pre-production. Don’t take anyone else’s word for what is going to work best for your film.

From a creative standpoint, you need to take into account the color process when making any key production decisions that may have an affect on your visuals. These include decisions on lighting, props, locations, wardrobe, and literally anything else that shows up on the screen. Remember that whatever look you are going to aim for in the color suite is going to either be helped or hurt by your work on set. So decide on the look you want up front, and let it have an influence on your creative visual choices along the way.

Following this basic logic during production will help you save countless hours in the color suite, which would otherwise be spent fixing issues or creating a look that wasn’t there to begin with.

CREATE A COLOR STRATEGY

Virtually every filmmaker with some degree of experience understands just how critical planning is to every stage of production and post. A writer isn’t going to type FADE IN:, until they have an outline. A director isn’t going to step on set without a shot list. So why would a colorist start their creative process without any sort of blueprint?

Unfortunately, color correction is often approached as a bit of a trial and error process, in which filmmakers will wing it – desperately searching for the right look along the way, without any sort of concrete plan or methodology. Working this way can result in a ridiculous amount of wasted time, which is mostly spent auditioning looks that are completely wrong for the film.

In an ideal scenario, a filmmaker’s basic plan for color correction would be in place before the film is even shot, as we already touched on above. This would provide consistent visual direction during production, and the same color strategy could then be carried over into post.

But let’s assume for a minute that you are a colorist that is working on someone else’s material that was shot without a strategy. You can (and should) still come up with your own color strategy during post-production… And it should begin before you even open up DaVinci.

At the very least, you’ll want to know what type of look you are after – Do you want something that looks heavily stylized? Or do you want a natural look? Should it look vintage? Or is a contemporary look more appropriate? These are basic questions that you should ask yourself up front. From there, you want to make decisions on the color palette as a whole: Warm vs. cold, saturated vs. desaturated, and so on. It’s also important that you understand which scenes or sections are going to be colored in any given way. Is your whole film going to have a color wash to it? Or do you want each scene to have it’s own look?

Ask these questions early on. Doing so will save you a ton of time that might otherwise be spent creating intricate looks that will likely later be abandoned.

UNDERSTAND THE ORDER OF OPERATIONS

As with any other part of your post-production pipeline, there is a standard workflow and protocol for color grading your project that will speed up your process substantially. This is usually referred to as your order of operations.

Just as an editor will pull selects first, then start working on an assembly cut, then move to a rough cut, and so forth – a colorist has a defined process as well. Once the picture is locked and the color session is set up, a colorist’s first step is to balance all of the shots. In other words, shots that have white balance issues, inconsistencies in contrast, or other general problems need to be addressed first. The goal is to get all of the footage to a neutral starting point before moving ahead with the more creative color work.

Many amateur colorists make the mistake of jumping right into their creative look before balancing their footage, and spend ten times longer coloring their projects than they would have if they followed the correct order of operations. This is because it is nearly impossible to apply a stylized look across a full sequence with any degree of consistency if the individual shots were not each balanced to begin with. A look that works well on one shot will not be able to be seamlessly applied to another in the same scene or sequence if they aren’t both matched before-hand. The result will be an inconsistent looking sequence of shots, and any attempt to fix these issues after the creative look has already been applied will be massively time consuming.

START WITH THE WIDE SHOT

Assuming you are color correcting a scene that has a wide angle shot in it, coloring that shot first will almost always serve as your best starting point.

Often times, colorists will simply start to color correct the very first shot in the scene, and then move sequentially throughout the rest of the scene or sequence, shot by shot. In some rare cases, this might work out just fine. But in many instances, especially when the first shot is a closeup, it will not offer the most efficient or effective workflow.

The issue with coloring a closeup or insert shot first, is that it’s not likely to showcase the full color palette of the scene. Say for instance you are grading a scene that features a man leaning against a tree. If you were to color the closeup first, you might only see his face and the blue sky behind him in the shot. This would lead you to make different color choices when compared to the wide shot, which would also reveal the brown tree, the green leaves, and other colorful details in the background.

So in a nutshell, to avoid wasted time when coloring any scene, always start with a wide shot – or at the very least the shot that has the most color information in it. From there, the look you’ve created should apply seamlessly to any other shot in that scene.

LIMIT MASKS & KEYS

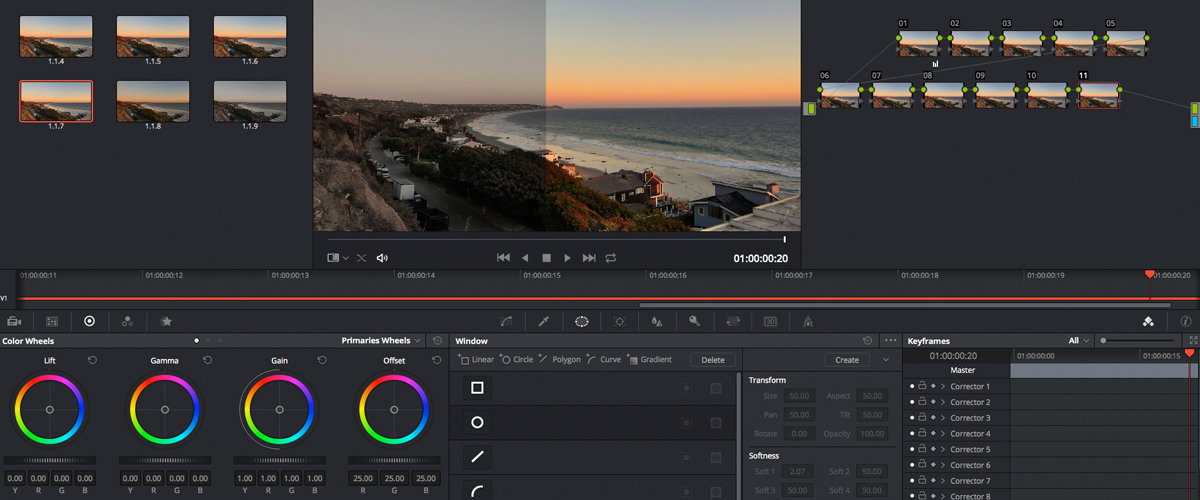

When you first start working with professional color correction software like DaVinci Resolve, it’s tempting to go a bit crazy with the use of masks and color keys. Once you realize how much you can use masks (power windows, vignettes, etc.) and color keys (selections of color that can be independently adjusted), the possibilities seem endless. You could practically change the lighting of a scene in post, or alter the color of someone’s clothing. There is so much that can be done, but pushing things too far can hurt your finished product dramatically.

As with many other facets of film, less is more when it comes to color grading. Even in instances where you are going for a really extreme or bold look, achieving this type of look (or any other for that matter) shouldn’t be overly complicated. Masks and color keys should not be relied on as a means to achieve any type of creative look that will be used over the course of your entire film… At least in my opinion. Instead, masks and keys should be used to enhance an existing look, or correct for certain issues that may occur in individual shots that have problem areas.

If you are coloring a feature film and get into the habit early on of pulling keys and adding masks to every single shot, your film is probably going to suffer. There are exceptions to this rule, but generally speaking your film will almost always look better by taking a simple, purposeful approach to your color process, as opposed to a highly technical one that is overly reliant on very specific corrections. This is because maintaining consistency across a 90 minute feature when pulling multiple keys in every shot is nearly impossible, and the time that it will take you to do so can be practically insurmountable.

USE LUTS

I am a huge advocate of using creative LUTs, and am constantly creating my own LUTs to use on projects as a means of speeding up my creative process. LUTs offer the ability to quickly add creative looks to your footage, which will not only allow you to work faster, but also to experiment with different styles in a highly effective way.

Earlier I spoke about how important it is to have a strategy when you begin your color process, which will certainly prove to be invaluable on any project. But no matter how much prep work you do, there will still be some creative interpretation that will be left to your color sessions. For instance, you might know that you want your scene to have a very warm look to it, but there are many different types of warm looks to choose from. Some are more orange, while others are more red. Some have cooler tones in the shadows to add color contrast, whereas others offer more of a warm color wash.

LUTs allow you to experiment with variations of looks very quickly and easily. You can simply apply one after another to your footage, until you find one that is closest to the look you are after. You may still want to tweak the color to customize the look even further, but the LUTs will have given you the ability to see so many different possibilities instantly, and save hours of time that could have spent experimenting manually.

Below is a quick demo video of a few of the LUTs from my “Genre Pack” applied to some real world footage:

TAKE BREAKS

Color correction should always be treated like a marathon, not a sprint. Your eyes literally get adjusted to the colors that you are staring at, and after a certain point when you have worked for too long, you just aren’t going to see clearly.

Many colorists make the mistake of sitting in the color suite for hours on end, only to look back at their work the next day and realize they need to re-do a lot of it. While it may be tempting to simply power through a color session and get your entire project done in one shot, it’s rarely that simple – unless you’re working on something extremely short, like a 30 second commercial.

For the most part, you need time away from your work to come back with fresh eyes and look at what you’ve done objectively. I typically recommend taking breaks in two different ways:

First, I always suggest not working for more than 2 hours without taking at least a 15 minute break to leave the room, go outside and let your eyes adjust. You will be amazed at how different your work will look when you come back.

I also like to recommend taking mini-breaks from your shots while coloring particular scenes, especially when you’re having a hard time getting into a groove. If you’re stuck on one shot for twenty minutes, chances are you should just move on to another shot and come back to it later. Either the shot you’re working on is already done and you are over-doing the color on it, or it needs a fresh perspective, which you won’t be able to give it since you’ve been staring at it for so long.

While taking breaks may seem like it would add time to your color process as opposed to tightening it up, in fact the opposite is true. Those small investments of time in the form breaks during or after your color session, will allow you to get to the finish line more efficiently in the long run.

That’s about it for now!

For more content like this, be sure to follow me on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter!

8 Comments

Skylar Williams

atThank you for your tip to not go overboard when using masks and color keys. I’m new to photoshop and color grading but I want to learn. I’ve got some film that I want to edit but I still need the software to do so. Once I get it I’ll be sure to keep calm when using masks and color keys.

Noam Kroll

atAwesome to hear, Skylar. Best of luck with your color grading!

Emmanuel Moran

atHey Noam, Thanks so much for all the helpful advice and tips. Something I’ve been grappling with has been the pros/cons of using an input lut. Lately I’ve been working a ton on fs7 footage with Slog3 footage and debating the efficacy of starting with a slog to 709 input lut. What are your thoughts on this in terms of simplifying the process. I know you are into using them as a final touch but what are your thoughts on using luts to convert slog, log c, et al using input luts?

Thanks!

Noam Kroll

atGreat question! Honestly, I almost never use an input LUT myself. Unless I’m coloring Alexa/Amira footage (as their LUT is bang on), I typically find I get better results by manually adding contrast and saturation to a log image… But that’s just me!

Arshjyot SINGH

atDear Noam,

I really feel helpful by reading your blog regularly & it helps me a lot in my day to day video making. I haven’t learned a lot from your blogs and articles.

I just have few questions regarding exporting video from premiere pro. I hope you can help me in it.

I noticed that my Canon 700D creates about 40-45 Mbps bit rate file for 1080p video. But when I export it after color correcting my video, I export in h.264 with a bit rate of 20-22. I notice there is the really huge difference in video quality. Then I tried exporting at a same bit rate of the original file. I exported it this time at 45-50 Mbps. Still, when I compared exported and original file, there was still a difference in both of them. No matter how high I went, the exported file look worse than the original (even if I exceeded the bitrate of the original file). But then I tried exporting the video in ‘Animation’ codec’ at highest settings. This time, the exported file looked exactly same as the original file. But the bit rate was near 300 Mbps.

These are few questions:

1. How can export the video with exact same quality of the original file, while maintaining low bit rate?

2. In which codec settings should I export if I want to save that project for future editing without loosing any quality for editing & grading?

3. In which codec setting I should deliver my final edit to my client for really high end best quality for viewing.?

4. Is there any other NLE which can help me getting best codec settings without compromising space? If yes, which one and what should be the settings?

Noam Kroll

atHi Arshjyot –

Thanks for the kind words! And I completely understand your frustration, and Premiere Pro is generally quite inconsistent with it’s H264 compression results – at least from my experience.

To answer your questions –

1. You might want to consider exporting with ProRes Proxy (if you are on a Mac), as it will have a relatively low bit rate but should help preserve your quality. Alternatively, you can experiment with some of the compression settings on your H264 export. For instance, you will likely get better results by choosing “CBR” over “VBR 1 Pass”.

2. I personally master everything to ProRes 422 HQ. It is virtually lossless, so although it is technically compressed, your eyes could never tell the difference. If you want to be really safe, ProRes 4444 is a good option too – especially if you not only want to master the file, but also be able to color grade it later on.

3. I would chat with your client about this. In some cases (for instance if your client is a production company), they may have a very specific deliverable requirement. In other cases (a corporate client), you might be better off delivering an easily playable H264.

4. Every NLE will essentially offer the same compression options (give or take), and the quality should be pretty similar across the board. That said, I do find that FCP X and DaVinci Resolve are better at encoding H264 than Premiere Pro.

Hope this helps!

Arshjyot SINGH

atHey man, thanks a lot for the reply. That was a really great piece of information. I’m a windows user, so I’ll try to export my projects through Davinci Resolve & see if there is any difference in size and video quality. Your reply was super fast. I really really appreciate that. Thanks a lot.

Just a side note. I read my original comment and noticed that I made a lot of typos.

Ugliest one was: “I haven’t learned a lot from your blogs and articles”

Correction: “I have*** learned a lot from your blogs and articles”

Thanks mate!

May God bless you with success…

Noam Kroll

atAny time man! Thanks so much again for the note, and looking forward to sharing more with you soon.

7 Ways To Speed Up Your Color Correction Process While Dramatically Improving Your Results – Filmmaker's Memory

at[…] http://noamkroll.com/7-ways-to-speed-up-your-color-correction-process-while-dramatically-improving-y… […]